Antique ceramics grace the mantels, furniture and windowsills throughout Hill-Stead. The soft greens of the Song [Sung] (960-1279) and Ming (1368 – 1644) Dynasty pieces on the Dining Room mantle were chosen to bring out the shades of green in Degas’ pastel, Jockeys, hung above it. The rich reds of the Qing [Ch’ing] Dynasty (1644-1911) sang-de-boeuf (oxblood) glazed porcelain on the Library mantle complement the Swiss Tortoise shell clock above. Striking 16th- to early 18th-century Italian Maiolica fills a cabinet in the Drawing Room.

Chinese ceramics

Chinese and Japanese wares were well represented in the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia. Within a decade or two, discerning collectors with means started purchasing antique Chinese pottery and Japanese woodblock prints. Mr. Pope, one of the earliest American collectors, started his collection in 1888, purchasing a beautiful Qing sang-de-boeuf bowl, the most popular of all the Qing dynasty single-color wares. The Han (206 BCE – 220 CE), Song and Ming Dynasties are also represented in the Museum’s collection. Mr. Pope continued to collect through 1907, when he bought a Chinese vase, a 6th-century BCE Corinthian pyxis and Japanese prints from Bing, Paris’ biggest promoter of Asian art, from whom Monet and other Impressionists bought their ceramics and prints.

Song Dynasty Celadon Jar

Porcelain jar in matte celadon green glaze, with carved wood lid

China, 960-1279

Height: 9 cm.; Diameter: 11 ½ cm.

The refined shape emphasizes the muted tones of the celadon glaze. By this period glaze properties were more systematically calculated, and kiln temperature and atmosphere more skillfully manipulated.

Song Dynasty celadon bulb bowl

China, 960-1279

Height 9 ½ cm, Diameter 27 ½ cm

This Chinese bulb bowl, or narcissus bowl, is very rare, possibly the best Asian piece in the Hill-Stead collection. The scalloped shapes and tri-pod feet of the narcissus bowls were made using a system of molds.

European ceramics

The Popes purchased numerous plates, urns and jars on their trips abroad. Pieces at Hill-Stead include many fine examples of 16th-and 17th-century Italian maiolica, English lusterware pottery, and the oldest item in the collection, a Corinthian head-pyxis, c. 570-590 BCE.

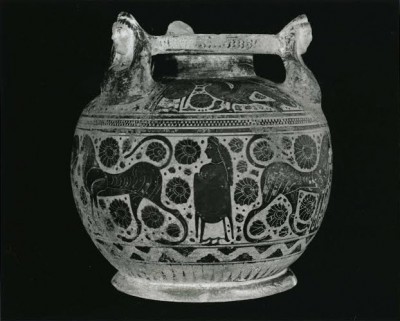

Jar, Head Pyxis

Jar, Head Pyxis

Earthenware, Corinthian, 570-590 BCE

Height: 9 1/8 in.

The ‘Head Pyxis’ is named for the three female heads at the top of the jar that serve as handles. This pyxis, originally used for cosmetics, toilet articles or jewelry, is the second largest head pyxis of only 76 known to exist. It is noteworthy for its excellent condition and profusion of ornament. This is the oldest item in the museum’s collection.

English Wedgwood Tea Set

English Wedgwood Tea Set

Glazed ceramic executed in rare yellow porcelain bisque, ca. 1810-1820

Manufactured by Josiah Wedgwood & Sons.

In the early 19th century, Chinoiserie was still prevalent in European decorative arts and Eastern styles greatly influenced the designs of textiles, ceramics, furniture and architecture. In the early 1800s, the Wedgwood factory was manufacturing a wide range of Eastern-influenced patterns to decorate dinner, dessert and tea wares. One of them was the ‘Prunus’ relief – Prunus is a genus of Japanese ornamental cherry tree – which decorates this pale yellow Wedgwood tea set in the Alfred Atmore Pope collection.

When Alfred and Ada Pope embarked on their Grand Tour in 1888-89, Japonisme was flourishing in Europe. While Alfred Pope was fervently collecting key works by the French Impressionist and Japanese masters, Ada Pope’s love of fine china and Asian-inspired decorative arts was evident in her purchase of the 15-piece Wedgwood Prunus-relief tea set. Today, visitors to Hill-Stead’s Second Library are drawn to the set’s distinctive color and decoration, qualities that surely captivated Ada Pope in 1889.

Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795) was one of England’s most renowned potters, credited with industrializing the manufacturing of pottery.

Italian Maiolica

Maiolica is the tin-glazed earthenware of the Italian Renaissance. The white opaque glaze, produced by the addition of tin oxide (powdery white ashes) to a lead glaze, covers the buff or red color of the clay to approximate the look of Chinese porcelain. Dipping the biscuit-fired piece in this tin glaze created a receptive base for painted decoration.

Maiolica made its first big appearance in America with 350 pieces in a gallery at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia. Alfred Pope was among the very first individual Americans to start collecting it. An archived receipt for maiolica shows two plates purchased in Venice during the family’s Grand tour in 1889, and the last receipt is for Urbino and Faenze pieces bought in Paris during the Popes’ last trip to Europe in 1907.

Istoriato Plate with Marcus Curtius

Maiolica pottery, probably Urbino or Castle Durante, ca. 1540-45

Height: 2 ½ cm.; Diameter: 22 ½ cm.

The istoriato, literally “storied,” or narrative style wares, emerged in the 16th century. The surface was painted like a canvas in an attempt to elevate maiolica to “fine art” status. Inspiration was often taken from ancient history and the classic legends. The story of Marcus Curtius represented on Hill-Stead’s plate is a very popular istoriato theme taken from Livy’s History of Rome: a great chasm opened on the Roman Forum, into which, the seers foretold, the Romans should throw their greatest strength in order to ensure that their empire would last forever. A young warrior, Marcus Curtius, mounted his horse and jumped into the chasm, claiming that youth was the most important thing.

Broad-rimmed bowl (tondino) with “peacock feather eye” design

Maiolica pottery, Deruta ware, 15th century

Height: 3 ½ cm.; Diameter: 23 ½ cm.

The best known achievement of the Deruta potters was their use of the iridescent metallic luster seen on this piece. In the beginning of the 16th century, they were most likely the first, and were definitely the most prolific, producers of the lusterwares. The metallic luster was achieved in a third, lower temperature firing. On Hill-Stead’s piece the design starts in the center with a small eight-petaled flower. In each row outward, the design is repeated slightly larger than the row preceding.