The museum’s collection includes 24 oriental rugs, many of which were originally purchased for the Popes’ home in Cleveland, Ohio. The rugs originate from three primary geographical areas in the Middle East: the Caucasus Mountain region, Persia, and Anatolia, all located between the Black Sea and the Persian Gulf. The Popes purchased these rugs primarily on their European travels, in the late 19th century, after the East had been made more accessible to Western merchants. The collection also includes five examples of American-made hooked rugs, an Arts & Crafts tradition that was a particular interest of Theodate’s.

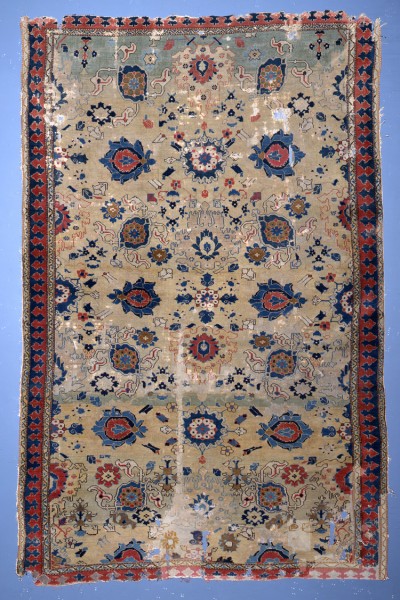

Transcaucasian: Probably Kurdistan

18th century

Caucasus Region

Approx. 5’ 5” x 8’ 3”

This rug is believed to be one of the oldest and most important rugs in the state of Connecticut, according to Joe Namnoun of J. Namnoun Oriental Rug Gallery, Hartford, CT. It appeared in the 1909 inventory of the Pope household and was situated in the master bedroom as a hearth rug. It is probable that this carpet was heavily repaired before being purchased by the Pope family, since many of the numerous restoration attempts appear to be well over 100 years old.

The design is commonly referred to as Harshag, meaning crab. It is a semi-geometric, Persian interpretation of the Herat design. This version of the pattern was developed during the 18th century as weavers moved from the south and east areas of Persia to the north and west. The principal motifs are the slanting palmettes which appear to “grow” into four, or sometimes two, split palmettes. In this rug the pattern is visible in the gold and blue designs with red offshoots, or tendrils, on a pale green ground.

The most remarkable images visible in this rug, which serve further in determining place and date, are the small flowering trees in the corners. At one end they are seen in red and blue and at the other end in blue and gold. The field is exquisite in its simple and spacious placement of flaming palmettes and other intricate devices. The trefoil design in the border is inverse in red and blue. Some experts support the theory that this design is reminiscent of 9th century Armenian Church cupolas. The age of this carpet can be best appreciated tactilely. It has a softness and fragility that only comes from the passage of time.

This rug is no longer on permanent display due to its extreme fragility. Nonetheless, it is a remarkable element of the collection and speaks to Alfred Pope’s exacting eye for quality and artistic composition.

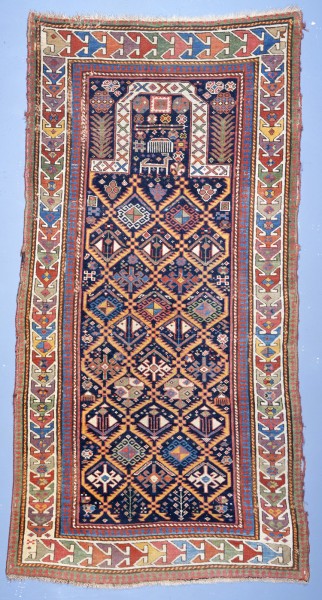

Shirvan Akstafa Prayer Rug

Last quarter of the 19th century

Eastern Caucasus Mountain Region

2’6″ x 5’2″

Akstafas, such as this example, exhibit traits that exemplify the era before mass production. In general, rugs from this region are rich with symbolism; animals, both real and mythological, human figures, and other images tell the story of folk life in the region. Noteworthy symbols in this particular rug are the stag at the bottom of the prayer gable or mihrab, the flowering trees at either side of the gable, and the comb drawing within the arch which is the Islamic symbol of cleanliness and purity. The field is a trellis filled with multicolored abstract floral and latch-hook motifs. The main border consists of a stylized, repeating calyx design surrounded by a trefoil pattern.

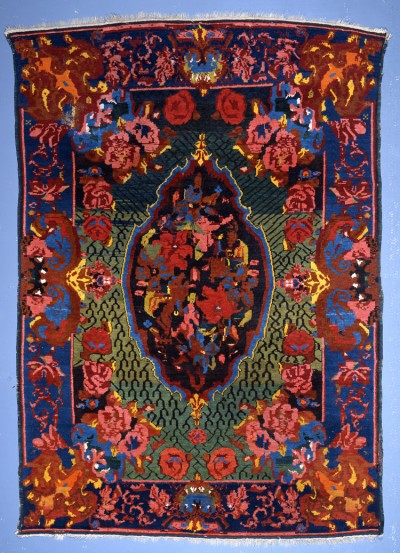

Karabagh

Late 19th century

Southern Caucasus Mountain Region

4’6″ x 6’4″

Rugs from the Karabagh region of the Southern Caucasus Mountain Region are characterized by primitive abstract geometric designs. Indicative of European influence, the floral motifs are somewhat crude compared to the Persian designs. While the design of this rug is typical, the rug is unusual in its bold coloring. On close observation, one can see 14 different colors, the work of an ambitious weaver. The arbitrary color variations are the result of a dyeing technique known as “abrash” in which wool is dyed at different times in different batches of color. This is most notable in the green field where the color density variation accounts for the striation which, in turn, enhances the artistic quality. The hooked-shaped motifs in the field could be interpreted as letters in the Armenian alphabet.

Sarouk (Arak)

Pre-World War II

Western Central Persia (Iran)

1’6″ x 2’4″

Sarouks are renowned as the best quality rugs from the Arak weaving district. This small mat, or poushti, made in Western Central Persia, was intended to withstand heavy traffic with its solid construction of some 200 knots per square inch. Early 20thcentury rugs commonly displayed linear floral designs as seen here. Later rugs bore the influence of Western design with elaborate floral designs. Once these later rugs were imported into the U.S., they were often enhanced by painting in pigment-rich dyes to intensify their coloration and make them more marketable. The simple design and unpainted navy field of this rug indicate that it was produced prior to World War II. The rug also bears a tag on the back with the name of the importer, his wash code number, and the date 11/8/35, which supports the dating theory based on design and dye technique. Given the date it seems likely this rug was acquired by Theodate and added to the collection of older rugs acquired by her parents.

Northwest Persian

Last quarter of the 19th century

Central Western Persia (Iran), Greater Hamadan Region

Piece #1 (left): 3’6″ x 7’5″

Piece #2 (right): 2’5″ x 4’5″

Originally these two carpet sections made up one rug approximately 3 ½ feet wide and 12 feet long. The seven medallions were in a symmetrical order of red, white, red, a center of saffron, and repeating red, white, red forms. Photographs from the Popes’ home in Cleveland, where they lived prior to settling in Farmington, suggest the rug was whole at that time. The reason for having the rug remade into two sections is not clear, but there are no apparent worn areas, suggesting that the rug was altered for a new, smaller space. On close inspection one can see the seam on the longer rug where it was segmented. The smaller rug has also been altered by removing the outer-most border, trimming lengthwise what would have been the inner border, and inverting the sections to create new end borders.

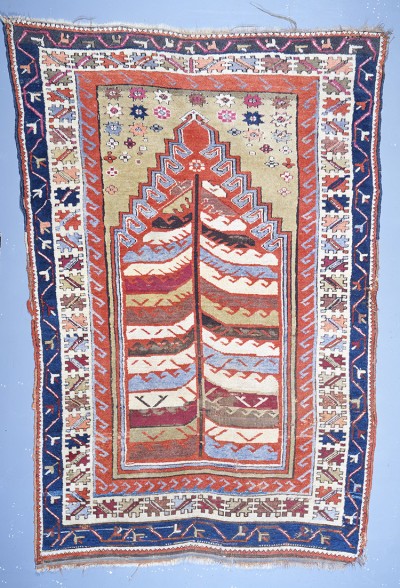

Anatolian Prayer Rug

Last quarter of the 19th century

Anatolian Plains of Turkey

3’3″ x 4’10”

This rug originates from the Anatolian Plains of Turkey, an area known for producing both secular and religious rugs. The unique green color in the field indicates the rug was possibly woven in the area of Kirshehir. The arch shape or mihrab that appears on all prayer rugs in various forms is made up of multi-colored leaf motifs that culminate in a latch hook design at the peak. The latch-hook pattern is repeated in the red inner border. The puzzle-piece geometric designs in the white border and the vinery in the blue border are both design elements popular in this geographic weaving area. Though woven for religious purposes, the artistry exhibited here in use of color and design elements is more common for a secular, decorative rug.

Hooked Rug

Last quarter of the 19th century

One of five in Hill-Stead’s Collection

Amy Mali Hicks wrote in The Craft of Hand-made Rugs (Empire Book Company, 1914) that hooked rugs were “the most important of the hand-made rugs.” Theodate brought Miss Hicks to Farmington from New York City in 1902 to teach rug hooking in her Sewing School which operated in the village from ca. 1901-1917. The origin of Hill-Stead’s five hooked rugs is not known but most of them are of various floral patterns, the most popular motif, and one geometric design. Hooked rugs are made by pulling strips of yarn or fabric through a linen or burlap backing to create a low, looped pile. These types of rugs originated in Europe, date to the 18th century in North America, but were not considered high style or suitable for Victorian-era homes and interest in them waned. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution and the Arts & Crafts Movement, cottage or village industries developed, and interest in rug hooking surged.