By Melanie Bourbeau

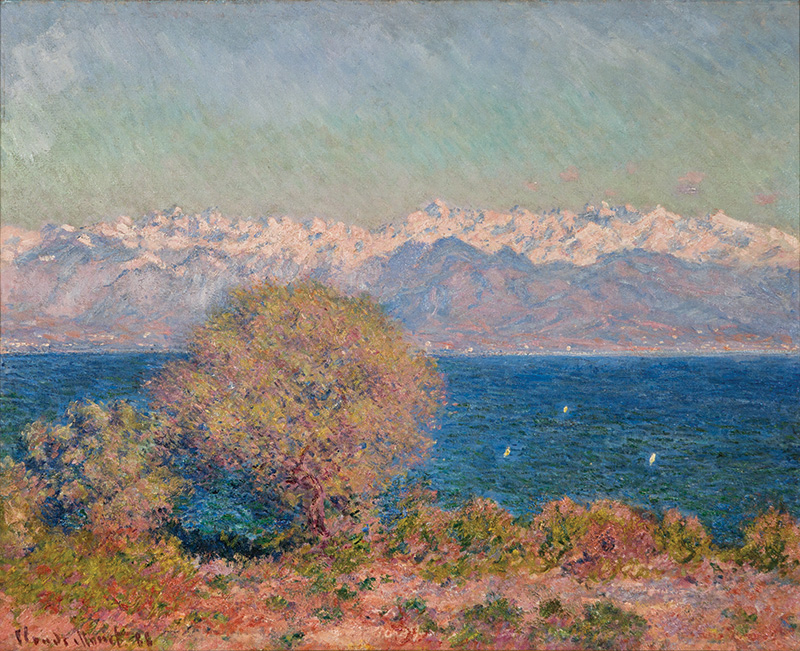

Hill-Stead Museum, in Farmington, Connecticut, was formed in 1946 (officially opening to the public in April 1947), when Alfred Atmore Pope’s daughter bequeathed the entirety of the household, including her father’s unparalleled collection of paintings. During Pope’s active collecting years (1889-1907) he amassed some 40+ works of art, the vast majority of which were French Impressionist. Due to Pope’s careful pruning through sales and exchanges, in order to retain only those works that elicited a profound emotional reaction, and his daughter’s subsequent dispositions, only a small fraction—albeit perhaps some of the finest—are part of the collection today.

Hill-Stead Museum, in Farmington, Connecticut, was formed in 1946 (officially opening to the public in April 1947), when Alfred Atmore Pope’s daughter bequeathed the entirety of the household, including her father’s unparalleled collection of paintings. During Pope’s active collecting years (1889-1907) he amassed some 40+ works of art, the vast majority of which were French Impressionist. Due to Pope’s careful pruning through sales and exchanges, in order to retain only those works that elicited a profound emotional reaction, and his daughter’s subsequent dispositions, only a small fraction—albeit perhaps some of the finest—are part of the collection today.

Pope, born on July 4, 1842, hailed from modest means. He was the son of a Quaker woolen mill operator. After working alongside his father and two brothers for several years, he came to the realization this was not the life he envisioned for himself. He secured his release from the family’s business obligations and borrowed funds to invest as an officer in the Cleveland Malleable Iron Company, a manufactory then specializing in agricultural-related products. Within a short time, and by the age of 37, he was appointed President of the company remaining at the helm until his death in 1913. He oversaw operations as the company grew exponentially with the advent of railroad expansion that resulted in development of an automatic coupling device, just one of many designs produced nationally.

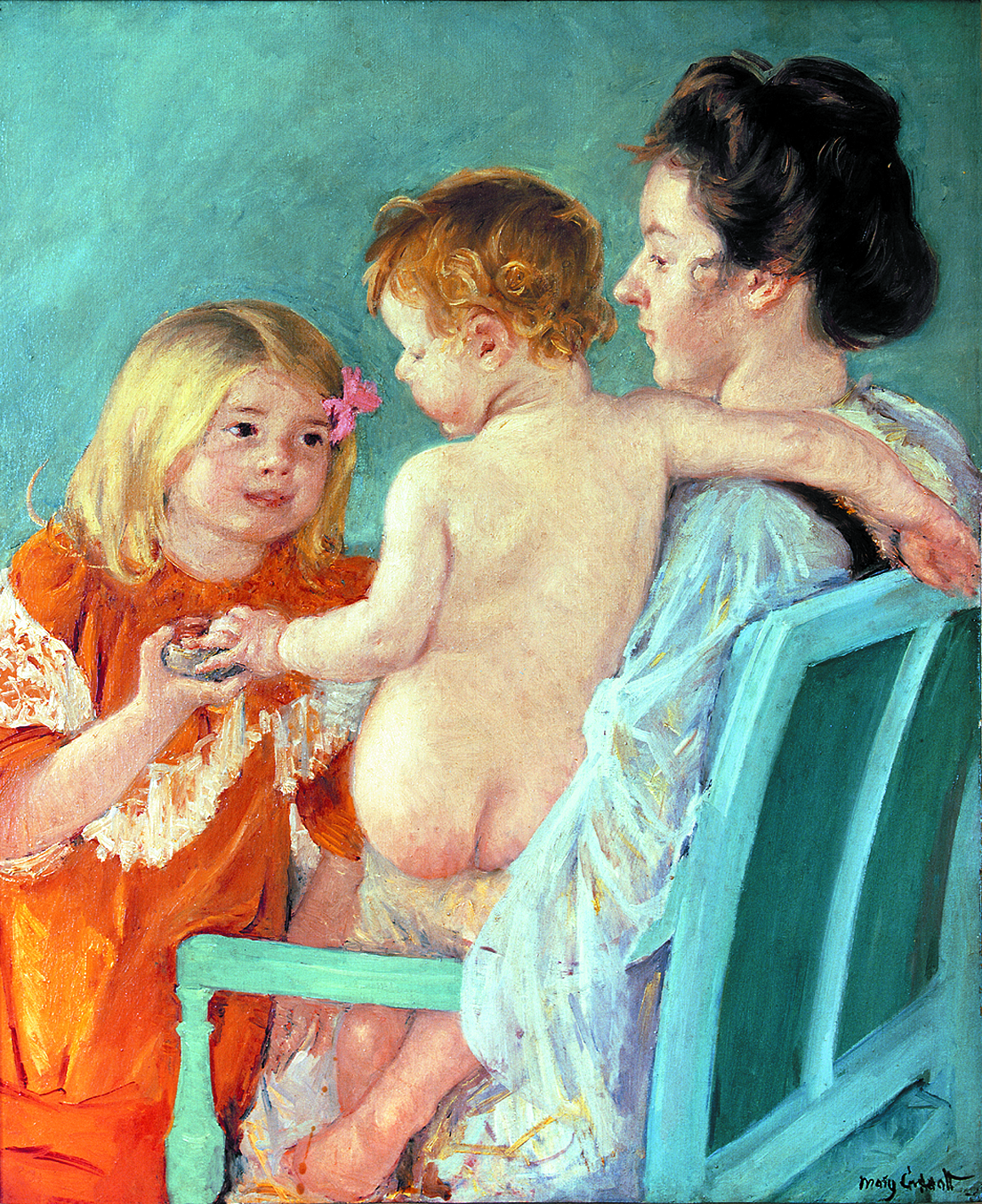

This early success in business matters laid the financial foundation that enabled Pope’s foray into the world of art collecting. Pope had no formal background or training in the arts. Of his own accord he honed his eye and developed an assurance in his convictions about what he saw at galleries and exhibitions in the U.S. and abroad. Though correspondence in Hill-Stead’s archive and other repositories suggests he did not rely on an advisor in any official capacity, recent scholarship shows that Mary Cassatt, whom the family met in the latter 1890s and knew on a deeply personal level, played a pivotal role in at least one acquisition. Pope also came to have a richly rewarding relationship with Whistler, over a brief period in the mid-1890s, but frequently followed his own instincts rather than bowing to Whistler’s recommendations. Unlike his more well-known contemporaries, Havemeyer and Palmer, who had massive collections that ran the gamut of movements, Pope eventually focused his efforts on acquiring examples of a new and radical contemporary art at the dawn of French Impressionism’s foothold in America.

- Photo by Anne Day.

- World-class Impressionist art

- The Blue Wave, Biarritz, James McNeil Whistler

Hill-Stead Museum would not exist without Pope’s collection as its heart, though much of the emphasis to date has been on his daughter Theodate Pope Riddle and her pioneering role as one of the country’s first female architects, whose design for the family home launched her career.