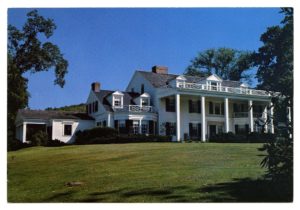

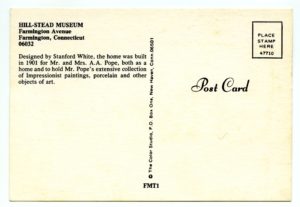

For a little more than half of its 75 years as a museum, Hill-Stead was misattributed as having been designed by Stanford White, as indicated by the credit on the reverse of this ca. 1980 postcard. By the mid-1980s processes and thoughts were beginning to evolve. In 1985 the first museum professional was hired to serve as Director; in 1986 the Pope-Riddle letters, documents and photographs began to be formally organized and catalogued; and in quick succession, a flurry of research ensued to broaden and deepen the story that had been shared with the public for forty years.

Still, the question of who really was responsible for the design of Hill-Stead dogged researchers for much of the 1980s.

There are just a small number of original letters between father and daughter referencing the plans for the new home in Farmington—eight letters from Alfred Pope to Theodate in the fall of 1898 and two letters from Theodate to her father in summer 1899. One such letter from Alfred to his daughter, dated Sept 5, 1898, notes his gladness that the property has been secured and that he and Theodate’s mother are “happy in your happiness.” He then advises Theodate to contact McKim, Mead and White and give to them “your plan” to get them to “assist” in deciding on location. Elsewhere in the letter Alfred wrote, “I think you should have the pick of your house place.” The tone and language of many of the other letters in this small group convey the sense that Theodate’s involvement in the project was more that of an agent for her father while he was abroad. Without the present-day hindsight of evidence that would come to light in later years, it is understandable why researchers back then were wary of how an untrained beginning architect could have pulled off this feat.

One phrase in one single letter, written by Theodate to her mother’s secretary while settling Ada Pope’s estate following her death in 1920 offers a definitive statement of Theodate’s involvement, in her own words: “I designed and superintended the building of the house…” Historians, however, look for corroborating evidence.

Two major “finds” began to solidify Theodate’s more than casual involvement. One was the return, in the mid-80s of Theodate’s long-lost dairies—except Hill-Stead did not know they were lost because no one knew they had ever existed in the first place! Following Theodate’s death and the immediate transition to a museum as her Will instructed, her secretary, who was uncertain about this plan, spirited away for safekeeping her diaries which had been kept intermittently from 1886-1905. The estate’s shepherd was deemed the best caretaker. During his last days while in a nursing facility, he casually asked one of his nurses what she thought he ought to do with them. Her reply, “I think the museum might like them back!” After painstaking transcription by one of Theodate’s cousins, this lengthy passage shed light on the depth of feeling Theodate gave to her chosen field of endeavor:

For years I have been keen on architecture and felt that the ugliness of our buildings actually menaced my happiness and felt breathlessly that I must help in the cause of good architecture. But I have wrung my soul dry in that direction over fathers house, in my great fatigue last summer when I had so much to decide I felt at the end–when my sickness came, that all power of decision was forever dead in me. And now I find that my material world is losing its power to please or harm me–it is not vital to me any more. I am turning in on myself and am finding my pleasure in the inner world which was my constant retreat when I was a child. That world then was meagerly furnished from my own imaginings but now I bring maturer thoughts and eager fancies and it promises to be a goodly habitation. I used to feel a frantic anxiety to uphold the best expressions in material art and felt that that was in itself enough to occupy ones life with. I might have known where I was tending–pictures have been dead long ago to me–the ones that please me, please only at first sight–after that they are paint and nothing more; to use a vulgar expression they are “sucked lemons.” My interest in architecture had always been more intense than my interest in any other art manifestation, and on my word I think it is not dead yet–not quite. If I only knew how to help the cause of good architecture! But I am tired of seeing these fluted flimsy highly colored hen houses going up–and am tired gnashing my teeth over them. I am just tired and sick of this work a day world which we see with our eyes and am turning to the world that I can be gate keeper of and admit what I choose. And nothing is too fine the dread question I ask myself now is anything fine enough, is the best thought of the best ages satisfying. Does Shakespeare, after fifty years of studying[,] pall on his students or can one find in him all ones days that restful unfathomableness that we crave?

The next “find” was in the McKim, Mead and White Papers—selected groupings at the New-York Historical Society and The Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, New York City. There is much correspondence between Theodate and the firm: 50 some documents comprising letters, sketches, and notes. Among them one showing Theodate, a novice, every bit in control of the massive undertaking of building a 33,000+ square foot estate:

Theodate’s initial letters included the salutation, “Dear Sirs,” addressing the firm collectively; eventually, she wrote directly to just one partner, William Rutherford Mead, and later as the project progressed, she switched to corresponding with associate architect in charge of the Hill-Stead job, Edgerton Swartwout. Never did she write solely to Stanford White, and in fact there is little to no evidence of White’s direct involvement in the Hill-Stead project. For many years, before research proved otherwise, it was simply an assumption based on White being the most notable member of the firm and having a larger-than-life persona that he was a major player in Hill-Stead’s formation.

In 1988, Leland M. Roth, architectural historian and Associate Professor and Head, Department of Art History (University of Oregon), visited Hill-Stead to meet with the director, Katherine Warwick. Roth had written a definitive book about McKim, Mead and White’s work in 1983, in it referencing Hill-Stead and the Pope family. In a letter to Warwick, Roth wrote that determining Hill-Stead’s rightful designer was a “knotty question” and one not easily “untangled.” He continued, Hill-Stead is a unique truly in the work of MMW not only for the architectural design but also because the client was so deeply involved in decision-making, a dynamic that had not occurred before or after. Hill-Stead, in Roth’s opinion, was a mingling of contributions. Roth believed that Stanford White very likely exercised general control over the project and may have been intrigued at designing a house for an impressive modern art collection but noted that it does not seem he participated in any direct way in design decisions.

By 1990, with the publication of Mark Allen Hewitt’s The Architect and the American Country House (Yale University Press), Theodate was beginning to be given the credit she so rightly deserved, but with a few caveats. Hewitt notes “There are several rather uncharacteristic aspects to the design of this house which point directly to Miss Pope’s ideas rather than to those of her architects.”

In 2010, James O’Gorman, in “Hill-Stead and Its Architect,” Hill-Stead the Country Place of Theodate Pope Riddle definitively positioned Theodate as designer of record.

This diary passage is Theodate’s reflection on her undertaking, upon completion of the project shortly after her parents moved into their new home:

This home seems strangely unreal to me. I feel as if I were walking in a dream and not in Farmington. It all seems so unlike the Farmington I have always known, everything up here, but it is all so very restful and beautiful I feel so at peace with the accomplishment of it.