Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926)

Mary Cassatt settled permanently in France in the 1870s when she was in her 30s. There she became friends with Edgar Degas and the Impressionists, and exhibited with them in four of their eight Impressionist Exhibitions held from 1874 to 1886 – the only American artist invited to do so. After 1900, Cassatt became known primarily as a painter of mothers and children.

Sara Handing a Toy to the Baby

Sara Handing a Toy to the Baby

Oil on canvas, ca. 1901

33 x 27 in. (83.8 x 68.6 cm)

Signature lower right: Mary Cassatt

In Sara Handing a Toy to the Baby, Cassatt employs compositional techniques used in Japanese prints, such as cropping both sides of the picture to give the viewer a glimpse of an intimate moment.

The Popes met Cassatt while she was on a visit to America in 1898. They continued their friendship with her on their visits to France, and hosted her at Hill-Stead in 1908. Mr. Pope began his collection of her work in 1894, eventually acquiring four oils, one pastel and one print. Only Sara Handing a Toy to the Baby and the print, Gathering Fruit, remain in the collection.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917)

Considered to be the best draughtsman of his generation, Degas called his work the result of “premeditated instantaneousness.” At least half of the mature work of Degas was devoted to dance subjects, resulting in approximately 1,500 drawings, prints, pastels and paintings. Jockeys and nudes of women bathing were his other popular subjects; all three are represented in Hill-Stead’s collection.

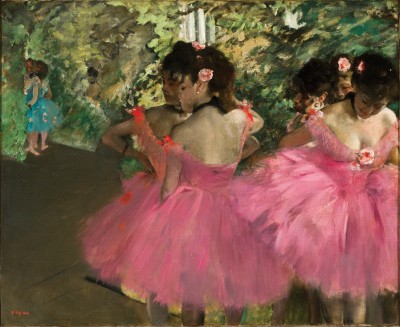

Dancers in Pink

Oil on canvas, ca. 1876

23¼ x 29¼ in. (59 x 74 cm)

Signature lower left: Degas

Ten years before Mr. Pope purchased Dancers in Pink from Cottier & Company, New York in 1893, it was exhibited in the Pedestal Fund Art Loan Exhibition in New York to raise money for the pedestal base for the Statue of Liberty. One critic remarked about the “… repulsively real ballet girls [but] magnificently brushed in.” Whether Degas was depicting nudes or dancers, he characteristically drew them in realistic, contemporary settings as opposed to the idealized, classical style that was accepted by the academics of his time.

Jockeys

Pastel on paper, 1886

15¼ x 34¾ in. (38.5 x 87.9 cm)

Inscribed lower right: Degas 86

There were two periods in the career of Edgar Degas when jockeys were the subjects of his work: first, in the 1860s, when Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann were rebuilding Paris and planning Longchamps, the finest racetrack in the world; and second, in the early 1880s, when his work reflected his interest in the study of movement, photography, and Japanese art. Jockeys is from the latter period, where the influence of Japanese woodblock prints is evident in the artist’s compositional technique, namely in the truncating of the figures and the use of a diagonal line of mounted jockeys to create a dynamic perspective against the horizontal plane of fields and sky.

Mr. Pope purchased Jockeys in 1892 when the family still lived in Cleveland, Ohio. When they moved to Hill-Stead in 1901, they installed the pastel over the mantel in the dining room, where visitors can see it today. Mr. Pope commissioned a new frame for the piece in 1907, designed by Herman Dudley Murphy of the Boston frame-makers, Carrig-Rohane.

The Tub

Pastel on blue-grey paper, ca. 1885-86

27½ x 27½ in. (69.9 x 69.9 cm)

Signature lower left: Degas

This work is one of the “Suite of nudes of women bathing, washing, drying, rubbing down, combing their hair or having it combed” that Degas created in preparation for the eighth and last exhibition of the Impressionists in 1886. Although it is not conclusive that The Tub was exhibited at that show, it is viewed today as one of the artist’s finest pastels. It is distinguished by his mastery at applying successive layers of pigment, his unconventional use of color whereby blues are as intense in the background as they are in the foreground, and his unusual bird’s eye view of a woman caught in an intimate moment as if, as Degas said, “… one were watching her through a keyhole.” This work, in its original Degas frame, was purchased by Mr. Pope in 1907 and was his last major art acquisition.

Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883)

Édouard Manet never considered himself an Impressionist and refused to show in the seven Impressionist Exhibitions held during his lifetime. Nevertheless, he was considered a leading figure in this avant-garde movement. Although he used classical subjects in his early work, he painted them in a new style, seen as irreverent and unacceptable to the art establishment and critics.

Toreadors

Oil on canvas, 1862-63

20¼ x 35¼ in. (52.3 x 89.6 cm)

Signature lower left: Manet

Always an admirer of Velázquez and Goya, Manet was influenced by the Spanish craze that swept Paris upon the arrival of Napoleon III’s Spanish wife, Eugénie. Within two years of the completion of Toreadors, Manet completed 15 other paintings with Spanish subjects and became known as the “Spanish Parisian.” The pendant to Hill-Stead’s oil is The Spanish Ballet (1862), now in The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Manet used some of the same props in both compositions, and both reflect the work of Velázquez in composition and palette.

The toreros pictured in this work had visited Paris in October of 1862. Manet asked the group to pose for him in the studio of a friend, Alfred Stevens. Upon his death in 1883, Manet’s widow gifted the painting to Mr. Stevens, who sold it soon after to London art dealer E.J. van Wisselingh. It was from this dealer that Mr. Pope purchased Toreadors in 1896, 13 years after the artist’s death, for approximately $5,000. Two years earlier he had paid a record-breaking $12,000 for another painting by Manet, The Guitar Player. The lack of modeling and contemporary scene in The Guitar Player and the sketchy, almost unfinished look of Toreadors elicited criticism for both of these works from the art “establishment.” Mr. Pope was not deterred, and added them to his growing art collection.

The Guitar Player

Oil on canvas, late 1866

25 x 31½ in. (63.5 x 80 cm)

Inscription lower left: Manet

The Guitar Player exemplifies Manet’s controversial “modern” approach, with its contemporary figure painted on a large canvas; a flat, two-dimensional picture plane; a sharp contrast of dark and light against a neutral background; and no idealized sentiment so prevalent in the accepted hierarchy of historical, religious and allegorical paintings at that time.

A year after Manet painted The Guitar Player, and knowing that he would not be invited to show in the official Universal Exhibition, he mounted his own solo exhibition of 50 works which included this painting along with earlier, often-ridiculed works such as Olympia, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, and Mlle V …in the Costume of an Espada. He used the same model, Victorine Meurent, in all of these controversial compositions.

Mr. Pope acquired this painting in 1894 from the Paris dealer Durand-Ruel for a record-breaking price of $12,000. (Manet had died about 11 years earlier, at age 51.) In a letter to his son in 1894, painter Camille Pissaro mentioned an American “nabob” who was willing to pay any price for a Manet that met his expectations, and the resulting purchase price of 75,000 francs caused “Amazement, far and wide!”

Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926)

Perhaps best known, and today, most popular among the Impressionist artists, Claude Monet’s early work Impression, Sunrise (1873) lead to the coining of the term. Monet was “keenly attuned to the natural world” and triumphed above early failures and slights to achieve his place in the highly competitive Parisian art world. His career spanned over 60 years evolving from realism uncharacteristic with how we see generally him in our mind’s eye to the mid-career works so well known to the highly abstract late waterlilies. Alfred Pope ultimately purchased nine works by Monet, four of which remain in the collection.

Fishing Boats at Sea

Fishing Boats at Sea

Oil on canvas, 1868

37½ x 50¾ in. (94.8 x 128.9 cm)

Signature lower left: Claude Monet

During the 1860s, a young Monet still in his twenties began developing a style that would eclipse that of his early mentors and painting companions. Although Fishing Boats at Sea was finished in the studio, it has the freshness of the plein-air style Monet practiced with Eugène Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind. It also employs a kind of coarse realism, as developed by his friend, Gustave Courbet. It is the broad brushwork, the unconventional flattened picture plane, and the harsh contrast of dark and light, (all techniques paralleling the work of the older Édouard Manet,) that made this work unacceptable for exhibit at the official 1869 Paris Salon. Undeterred by the rejection of academics, Monet continued to develop his unique style, and, during the next decade, moved away from seascapes and other traditional subject matter toward explorations of the impact of transitory light, weather, and atmosphere on a subject.

Though the earliest of Monet’s paintings in Hill-Stead’s collection, Fishing Boats at Sea was the last Monet that Alfred Pope bought, acquiring it from Durand-Ruel in Paris in 1894. In 1907, Mr. Pope commissioned a Herman Dudley Murphy-designed frame for Fishing Boats at Sea from the Carrig-Rohane Shop in Boston.

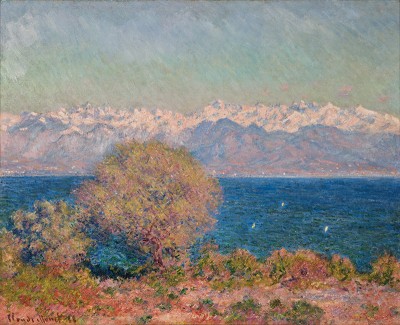

View of Cap d’Antibes

View of Cap d’Antibes

Oil on canvas, 1888

25¾ x 31¾ in. (65.4 x 80.6 cm)

Inscription lower left: Claude Monet 88

Monet did not join the Impressionists in their last joint exhibition in Paris in 1886. Instead he began to take advantage of the expanded railway system and traveled throughout France, from the rugged Atlantic coast of Brittany to the warm Mediterranean and the Cap d’Antibes, in search of subjects that evidenced his ties to the French countryside. At Antibes, he painted a group of 35 canvases that captured the jewel-like tones of that sunny region in thick paint and short, almost “pointillistic” brushstrokes. Hill-Stead’s View of Cap d’Antibes is one of these examples.

In Paris, Théo van Gogh bought and exhibited ten of Monet’s Antibes canvases at Boussod, Valadon & Cie, and it was there that Mr. Pope purchased Cap d’Antibes in 1889 during the family’s Grand Tour, his first Monet purchase.

At the beginning of this 10-month tour, Theodate wrote in her diary that the work by the Impressionists is “just stuff.” By the time they purchased this work seven months later, she wrote, “Did not like the Monet [Antibes] at first, but now I think it is the finest impression I have yet seen. We could not appreciate it had we not been in the Midi [the South of France].” This acquisition marked the beginning of Mr. Pope’s collection of works by the Impressionists.

Photo by R. J. Phil

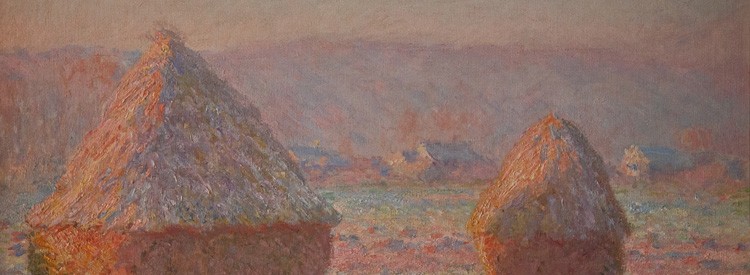

Grainstacks, White Frost Effect

Oil on canvas, 1889

25 x 36 in. (64 x 91.3 cm)

Inscription lower left: Claude Monet 89

By the time Monet painted Grainstacks, White Frost Effect, the Impressionists had already staged their final group exhibition in Paris in 1886; Pointillism and Neo-Impressionism had become the new avant-garde; and Monet, in his late 40s, was viewed as an established artist. Now, instead of traveling to tourist destinations to paint, he could turn to subjects near to him at Giverny—fields of poppies, the river Epte, and grainstacks.

In 1888–1889, Monet painted three canvases depicting two identical grainstacks, then two more paintings of single grainstacks. Grainstacks, White Frost Effect was one of the first three and Monet included it in a joint exhibition with Auguste Rodin at Galerie Georges Petit in the summer of 1889. Mr. Pope first saw Grainstacks, White Frost Effect on August 16 at this exhibition. Dealers Boussod, Valadon et Cie, Paris, had purchased it in June 1889 from Monet for 2,500 francs (approx. $500). And within a short time collector Stany Oppenheim, Paris, purchased this painting for 4,500 francs just days before the exhibition opened. Following the exhibition, Oppenheim returned the painting to Boussod, Valadon & Cie, who bought it back for 6,500 francs; Oppenheim essentially never took possession of the artwork. Boussod, Valadon & Cie then sold the painting to Alfred Pope on August 19, 1889, for 10,350 francs (approx. $2000).

Photo by R. J. Phil

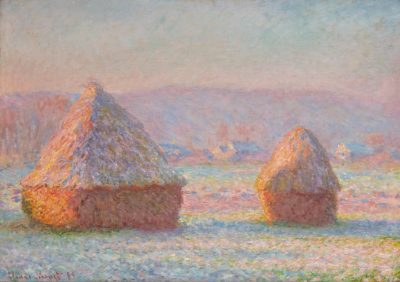

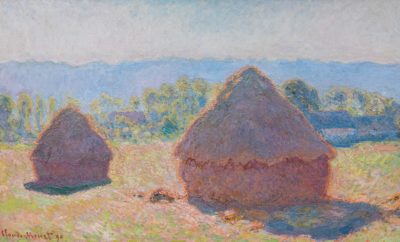

Grainstacks, in Bright Sunlight

Oil on canvas, 1890

23 x 38 in. (58.4 x 96.5 cm)

Inscription lower left: Claude Monet 90

A year later, in 1890, Monet began his familiar suite of 25 Grainstack paintings, soon followed by the Poplar series, then a series showing the Rouen Cathedral, the Thames, and finally, the best known, the Water Lily paintings. With the series of 25 Grainstack paintings, Monet was trying to capture what he called “instantaneity” or the effect of the “envelope of light and atmosphere” that defined an object. To do this, he painted the stacks near his home at Giverny throughout the spring, summer, fall, and winter of 1890-91, intending to exhibit the finished paintings together to maintain unity and coherence. The canvases are basically divided into three parallel bands representing field, hills, and sky. These horizontal bands are linked together not only by color but by the strong geometric, conical forms of the grainstacks and the roof ridges beyond. An innovative halo of backlighting, in Hill-Stead’s example, outlines the shape of the stacks to maintain their identity. Fifteen of the 25 grainstack paintings were exhibited by the dealer Durand-Ruel in Paris in May 1891. All were sold in three days.

Learn more about Monet’s Grainstacks through our virtual exhibition.